Transgressing in Video: An Orientation

“Oh, the night is my world,” Laura Branigan contemplates in her 1984 hit song “Self Control.” Casually transforming time into space, she discloses a rapacious desire to escape the daylight’s dull monotony. In doing so, Branigan speaks of transgression, the crossing of boundaries, be it between day and night, the regular and the extraordinary, or the street and the disco. While this idea is already ingrained in the song itself, it truly germinates in the accompanying music video. Over the course of five minutes, Branigan moves through a variety of settings in her quest to elope from her unsatisfactory daytime routine. By no means random, the selection of places as well as the manner in which they are traversed by Branigan and the camera and assembled by the editing team, all contribute to how viewers experience them. In this article, I argue that the video re-fashions the explicitly queer, Black spaces of the disco era through emerging conventions in the domains of mise-en-scène, cinematography, and editing. As a result, queer transgressive spaces are propagated to the implied audience of white, suburban teenage girls as spaces of liberation from the social sanctioning of bodily expression and sexuality but are concurrently rendered abstract and unreachable. The physical disco space is deferred to the virtual medium of the music video, a medium that was proving to be commercially viable for the record industry and its new prodigy project: MTV.

To prepare my reading of the music video, I will first introduce the theoretical and historical context, including the disco era and its spatial and ideological innovations, the conservative climate regarding feminism in the 1980s, the founding of MTV, and the codes and conventions of the music video as a genre. I then lead into my close reading by sketching out the medial discourse that surrounded the release of “Self Control.” Subsequently, I trace how the video distorts and alters the disco space on three filmic levels: setting, cinematography, and editing. Throughout, I connect these stylistic choices to my reflections on music video conventions, mediations of femininity, and the business mission of MTV.

The Post-Disco Era, the Rise of Anti-Feminism and the Rise of Music Television

The musical landscape of 1984, when “Self Control” entered the market, sits firmly in what Simon Reynolds calls the “post-disco era.” This wording insinuates that the era was defined by a detachment from, but also the lingering presence of, disco. The term disco here refers both to a music genre popular during the 1970s and its primary space of consumption. Disco emerged as a subcultural movement in Black, Hispanic, and queer urban communities during the late 1960s. As a music genre it blends traditionally Black styles of music such as Motown, Funk, and Soul with elements of Latin or European classical music. Its popularity grew throughout the 1970s, becoming the go-to soundtrack for the all-American dancefloor in the second half of the decade (Ray 165).

A highly influential discussion of disco stems from British academic Richard Dyer. In his 1979 article “In Defence of Disco” he countered the popular sentiment of disco as a hedonist, superficial, and consumerist vehicle of late-stage capitalism. On the contrary, he detects transgressive dimensions in disco music on a musical and cultural level, particularly in its approach to eroticism and romanticism (410). Dyer sees the eroticism of disco as “whole-body eroticism,” created by sexual lyrics, repetitively entrancing instrumentals and rhythms that provoke frenetic movement (411). Dyer’s whole-body eroticism extends sexuality in music from the phallus to the entire body (411).1 A second tenet is that of romanticism. According to Dyer, disco provides the musical backdrop for romantic moments of escape and transcendence. Thus, it offers an alternative to the everyday mundanity and attributes significance to the sphere of leisure as the primary site of personal meaning-making (413). Engaging with Dyer’s article in 2014, Luis-Manuel Garcia expands on the spatial dimensions of transgression in the disco. For Garcia, disco dancefloors were enacted utopias: places where physical bodies could move differently than elsewhere, where community and joy could be experienced, and the concerns of the outside world could be put aside (1). Garcia proposes to read dancefloors as “interstitial […] and fleeting” sites with a fundamentally utopian outlook (3). This notion is paralleled by Nadine Hubbs’ queer reading of Gloria Gaynor’s disco song “I Will Survive.” Hubbs compares the queer disco dancefloor to the medieval carnival, as both are a form of experimental space that temporarily suspends existing social systems, especially those of hierarchy and oppression (239-40). Dyer, Garcia, and Hubbs share the idea that the disco era created explicitly queer spaces and media which could suspend oppressive social relations for a limited time and experiment with innovative forms of expression.

Disco disappeared from the record shelves as quickly as it had conquered them. In 1979, the “Disco Sucks” movement formed, culminating most publicly in the Disco Demolition Night, an event during which visitors of a baseball game destroyed and burned copious quantities of disco records to proclaim the end of the genre’s reign over popular music. According to Gillian Frank, the protesters directly criticized disco for its public celebration of queerness (279). The campaign succeeded in ceasing disco’s domination of the music market, with disco sounds, images, and ideas mostly relinquished by 1981. However, the era’s legacy remained in the popular music that followed.2 In Frank’s article, the demise of disco contributes to the emergence of a new conservatism in the early 1980s. Outlining the cultural politics of that decade, G. Thompson refers to what he calls the “culture wars” during the presidency of Ronald Reagan (30). He states that the “culture wars” were fought between a largely white, male supporter base for Reagan’s conservative politics of anti-feminism, anti-multiculturalism, and anti-queer rights and the groups marginalized by them: women, queer people, Black Americans, ethnic minorities, among others. In her 1991 book Backlash, Susan Faludi pillories the anti-feminism of the 1980s. Her main claim is that feminism was often presented and perceived as a finished project that was supposedly beginning to cause women to be unhappy with their freedom (1-2). Faludi accuses the mass media of contributing heavily to this negative image (90). She traces how they adopted ideas of the new right and propagated them to the American public, cementing the image of the successful but unsatisfied businesswoman yearning to return to her family (91). Following Faludi, the 1980s created a hostile climate for messages of female emancipation.

However, there are also cultural moments that counterbalance Faludi’s grim assessment. Early MTV, for example, provides instances of women’s transgressions during the 1980s. Lisa Lewis first explored this from a scholarly perspective. In her 1992 article, she undertakes a semiotic analysis of several early female music videos, looking for visual signs of female address. She finds empowering female address most prominently in the usage of street space as a setting, a space perceived by her as hegemonically male (118). Through the manner in which they behave on the streets, dancing, walking with confidence, Cindy Lauper, Pat Benatar, and Tina Turner symbolically reclaim the street for women (118-20). Lewis clarifies, however, that these examples of empowering female address on MTV contrast a dominant sign system of adolescent male address (116). She closes by proposing a complex reading of MTV as a contested space where gender roles are both reinforced and questioned (126). This idea is expanded upon by Kenneth Shonk and Daniel Robert McClure. In their eyes, MTV offered a space for women to “transgress traditional representations and expectations” (172). They also situate early MTV in a period of transition between second- and third-wave feminism. Unlike second-wave feminism, women-fronted music videos in the 1980s framed issues such as sexual explicitness and longing for men as not inherently opposed to feminism (Shonk and McClure 178). The authors encounter further distinctly third-wave notions like a complex reconciliation of transgression and conformity, a working within structures instead of their demolition, and an acknowledgement of femininity as multifaceted (174). However, Shonk and McClure characterize the feminism of early MTV as “quiet,” meaning not a call to direct action but rather a space to envision alternatives and possibilities (175). Both Lewis, and Shonk and McClure emphasize how female videos offered moments of gender-based transgression but remain situated within a larger patriarchal structure.

The MTV project is relevant for my discussion of “Self Control” on a broader level than just its mediation of femininity, however. MTV, which started broadcasting in 1981, is the vehicle that catapulted the music video medium to fame. Underlaying soundtracks with video material was in itself not a new concept (Korsgaard 18; Marks and Tannenbaum 6-7). Rather, the unique appeal of MTV consisted of its specific targeting of a white suburban teenage demographic, to which it sold not only songs, but also an idea of juvenile irreverence. Graham Thompson sees MTV as an attempt to reclaim lost ground and revitalize the industry from an economic crisis (127). To achieve this goal, record executives decided to target a yet unexplored audience: the American teenager (Thompson 58). Amanda Ann Klein narrows MTV’s core demographic down to “white, suburban Americans of the ages twelve to thirty-four” (24), later adding middle-class to the mix (32). How this specific target audience was appealed to is explored by Craig Marks and Rob Tannenbaum in their account of young MTV. They outline an aesthetic of “quick cuts, celebrations of youth, shock value, impermanence and beauty” (2) that captivated teenagers and made MTV the “clubhouse” of that generation (2). Moreover, they observe a certain selection of features and traits characteristic to the early music video, including “aggressive directorship, contemporary editing and FX [special effects], sexuality, vivid colors, urgent movement, nonsensical juxtapositions, provocation, frolic” (8). What they provide here is essentially a first attempt at describing the genre conventions of music video that were coined during MTV’s early years.

Scholars of various disciplines have likewise attended to the task of outlining codes and conventions that govern the music video as a genre. A common observation is that meaning in music video is created in a unique manner. Carol Vernallis emphasizes the narrative contrast between music video and literature or classical cinema: While some videos do feature such narrative elements, they mostly fail to create stories in the Aristotelian sense of a coherent string of events which causally relate to one another (Vernallis 3). Instead, Vernallis proposes that music videos perform a “consideration of a topic rather than an enactment of it” (3). Another characteristic trait of music videos is their foregrounding of formal elements. While classical cinema often attempts to obfuscate techniques such as editing and lighting, these are brought to the forefront by music video and often carry meaning by themselves (112). Vernallis also introduces an array of ideas and observations useful for working with spatial aspects of music videos. In her book Experiencing Music Video (2004), she discusses music video space as imbued with “possibility, autonomy and prowess” that contrast with everyday life’s “patterns of repetition and stasis” (109). This space is erected through several filmic parameters. One of these is editing, meaning the selection and arrangement of shots (Bordwell et al. 217). Vernallis elaborates how music video shots are often conjoined by curious techniques, with cameras seemingly moving through solid structures, tiny openings, or screens (119). In this way, the camera exceeds human possibilities of moving through space and becomes oblivious to borders, impenetrable barriers, or size requirements. A further escalation of this is an ubiquitous use of the Kuleshov effect, a technique that arranges two shots filmed in separate locations in such a way that a spatial connection is implied (114).

Setting is also a parameter given special attention by Vernallis, although not under the umbrella of space, but place. Cultural geographer Yi-Fu Tuan understands space as a more abstract concept than place (6). Places are results of a process of accustoming; they have familiarity. Conversely, places are also more universal and grounded in convention whereas space seems to be first and foremost grounded in experience. Accordingly, the influence of editing remains largely spatial as it seems weird and unfamiliar. Setting, in contrast, works with places and prop configurations that are recognizable to the viewer. This effect, Vernallis explains, finds ample use by music video producers (82; 85). However, setting cannot only reproduce pre-existing places but meddle with perceptions of space as well (an aspect exemplified by the prop design in Branigan’s “Self Control” in particular). As a last argument about space in music video, Vernallis expands on how music video space is centered on bodies in movement through the means of staging, lighting, and cinematography. In Vernallis’s view of music videos, bodies and spaces become closely intertwined, suggesting that the detailed explorations of bodies can exalt sexuality and free viewers from bodily constraints, ultimately unleashing a liberating potential (98; 116).

Following Vernallis, music video space is a curious thing: It is antipodal to everyday space, because it upsets spatial logics, unlocks new possibilities, and never rests. It is centered on a body which rules over it. Spatial effects in Vernallis’s argument are controlled either by technical conditions or directorial decisions. Taking into consideration the historical context, meaning the legacy of disco music and its own ideas about space, the hostile climate towards female emancipation and the profit-driven targeting of MTV provides a promising opportunity to contextualize and add an explanatory dimension to Vernallis’s theories.

Reading “Self Control” between Robotic Commercialism and Emancipatory Eroticism

Among the female popstars of the 1980s, the name of Laura Branigan may not be the first to enter most people’s minds. Regardless, at least two singles of hers, “Gloria” and “Self Control,” have safely entered the 1980s pop canon. Branigan’s music is hard to assign to a genre. While “Gloria,” her first hit, has largely been seen as a late offspring of disco, other singles like “Solitaire,” “Spanish Eddie,” or “Self Control” are labelled synth-pop, post-disco, or Italo-disco. In the music industry magazine Cash Box, Peter Holden maintains that Branigan after “Gloria” was not marketed as a disco act, but still managed to sustain a following from her disco dawn. Dennis Hunt of the Indianapolis News agrees that Branigan is clearly an heir of a disco legacy, especially identifying similarities with disco diva Donna Summer. It seems evident that Branigan and her music were looked at through a post-disco lens. Branigan’s reception in the press oscillated between disdainful shunning of her perceived dullness and awestruck appreciation of her strong vocals and broad appeal. Holden commends Branigan’s appealing visuals, referring both to her looks and her music videos. He also describes her as the ideal artist for a record label because she was just distinctive enough to be recognizable without losing mainstream appeal. Hunt, more pejoratively, calls Branigan a “pet project of the label’s chief executive.” An even more scathing critique is formulated by Jim Sullivan for the Boston Globe, who likens Branigan to the Stepford Wives (Bryan Forbes, 1975) in her persona’s subservience to patriarchal desires. Praising figures such as Debbie Harry and Tina Turner, Sullivan finds Branigan and her music lifeless and dull.

The question of which image of femininity Branigan represents is especially pertinent to “Self Control.” The music video for “Self Control” was only published in a censored version because it featured shots deemed too sexually explicit. Branigan herself reflects on this in an interview with Entertainment Tonight, claiming that her sensuality is not a conscious attempt to seduce, but rather an intrinsic quality she possesses (“Laura Branigan: [[cc]]” 0:17-31). Subsequently, she expresses displeasure that the “orgy-type scene” (0:54) could not be aired freely, questioning the double standards on physicality in culture (2:08-28). The interview also raises another novelty of “Self Control”: The video was made by Hollywood director William Friedkin. This, Branigan reports, was a creative process that felt more like shooting a movie than a simple montage of performance clips and enabled her to execute her own artistic vision (1:44-59).

These views of Branigan and “Self Control” – which include the disco legacy, the song’s reception as explicitly commercial, its foregrounded sexuality, and its strong directorial voice – directly influence the representation of space in the music video. The young white female suburban target demographic of the video as well as the social climate of backlash against feminism also matter here, as “Self Control” presents to its audience transgressive spaces of escape. However, it does not locate these spaces in the sphere of attainability, but rather fictionalizes and obscures them, so that they remain within the music video. This process is present on three medial levels. First, through its settings, the video constructs a day-night cycle of escape but adorns it with props that remove it from a reality of experience and foreground its fictionality. Secondly, the cinematographic portrayal of Branigan, in tandem with her staging, constructs Branigan as emancipated and assertive but also sanctions her acts of transgression. Finally, editing is used to overcome spatial constraints, obscure spatial relations, and further signal the fictionality of the presented spaces.

“Tomorrow Never Comes”: Reading the Setting

The settings of “Self Control” essentially form a circle. Viewers follow Branigan from her bedroom to the street, into a club, down into its basement, through empty hallways back to her bedroom. Vernallis purports that music videos that feature a serial arrangement of settings ascribe mobility and, as a result, power to the performer (85). While the arrangement of settings in “Self Control” superficially conforms to this, other directorial choices complicate this notion, as the video establishes a more complex idea of spatial transgression by employing the technique of abstraction.

The settings in “Self Control” are places in Yi-Fu Tuan’s sense, compositions familiar by convention. Branigan enters the camera’s vision in her bedroom, lying on a chaise longue, wearing a nightgown (fig. 1). The bedroom as a place contains notions of the banal and the tantalizing, of sexuality and slumber. This room is adorned with flowers displayed in a fragile vase, a puppet clad in lace, curtains, a Persian rug, large bed side lights, and a naked man stretched out on the bed behind Branigan (0:03-20). Here, the director opts for props that evoke domesticity, fragility, and infantile innocence, such as fragrant flowers, dainty puppets, and delicate fabrics. Peeking through flowered curtains, Branigan then sees a silhouette of a city at nightfall (0:24-27) and decides to leave this room, taking to the mirror to dress up and paint her face.

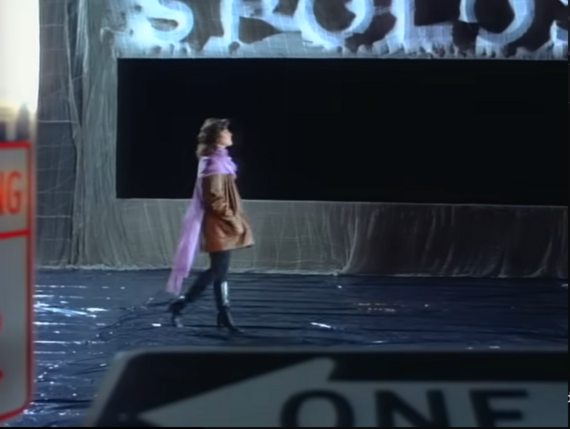

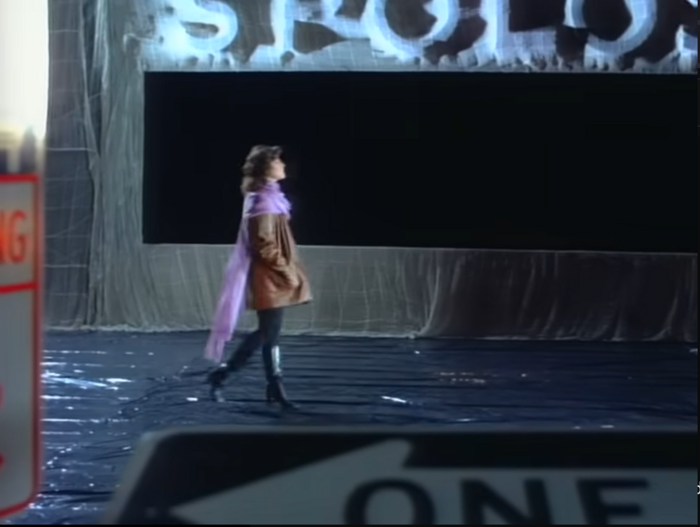

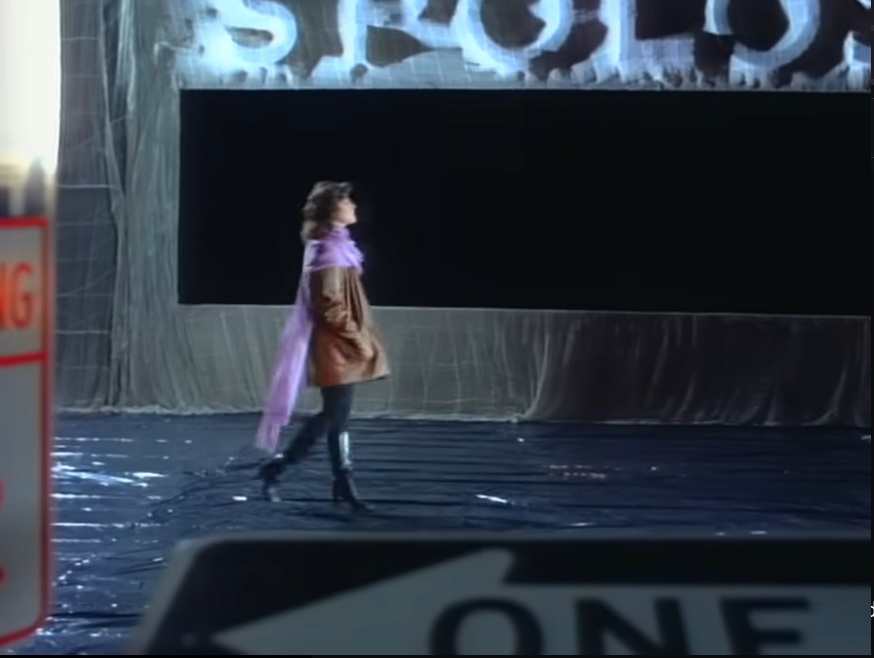

The next larger setting is a nighttime street complete with houses on the sides, traversing cars, and construction signs (fig. 2). Present as well are several passersby, including a gay couple, a group of young boys and a heterosexual couple with the veiled woman’s legs enclosing the man’s body. While the street is not presented as a space of male aggression, like the one Lewis detects in the music video for Pat Benatar’s 1983 song “Love Is A Battlefield” (119), it carries an air of hostility and that puts a stop to the earlier visuals of flowery daintiness. The scene furthermore occupies a peripheral position as accompaniment to the song’s bridge. As the bridge leads to the chorus, the street also leads somewhere else, another site that is presented as more important. The scene thus forms a first step of transgression away from the comfortable but uninspiring domestic environment, but its transitory nature is never questioned.

The first chorus is set to a bar scene, featuring gambling and dancing. On the dancefloor, Branigan is surrounded by various men in suits and ties, and the occasional woman dressed in red (fig. 3). This disco has little in common with the queer spaces of escape and transcendence established in the late 1970s. Instead of wearing colorful and flowing garments, these dancers seem as if not much separates them from their work-life selves. Branigan leaves this space quickly, too, and descends a stairway to the basement. The club is thereby no longer the destination but a steppingstone, just another place of transit.

In the basement, as the first verse is repeated, Branigan enters the orgy responsible for the video undergoing censorship. The spacious room is furnished with bathtubs, scaffolding, and a floor covered in aluminum foil (fig. 4). The people active in the orgy-like event are wearing skintight suits of pastel colors: light blue, violet, beige. Their face masks are reminiscent of the Venetian carnival, one is playing the cello, and there is a basket of fresh apples. As Nadine Hubbs remarks, disco dancefloors functioned similarly to the carnivals of Catholic Europe, because they “collaps[e] […] and revers[e] […] social norms, hierarchies and castes” (239). In the orgy scene, castes and categories are also ousted by uniform dress and the obfuscation of faces. Apples, bathtubs, and instruments evoke splendor, indulgence, and abundance. Arms and legs are stretching out in all conceivable directions with no regard for straight lines, preserving Dyer’s whole-body eroticism in positions where all body parts touch and interact. It appears as if the disco space of transgression has relocated from the dancefloor to the basement: the glittering disco ball has figuratively fallen down one storey and been dispersed throughout the room, transforming into an aluminum foil-like floor covering of a similarly reflective quality.

Before returning to her bedroom, Branigan stumbles down a white hallway, where the orgy visitors are still around her. As she then re-enters her bedroom, these “creatures” have followed her, teleporting in and out of sight, undressing her, and finally assembling in the masked, muscled man she goes to bed with. As he leaves through the window and sunlight enters the chamber, Branigan switches off the light and the scene returns to its outset.

A common feature of all the settings (the bedroom, the street, the club, the basement) is that the prop work is rich enough to immerse viewers and unmistakably signify Branigan’s place, yet sparse enough to set these places apart from their real-life inspirations. Branigan’s bedroom is characterized by a lack of wallpaper and exposed bare concrete, haphazardly hidden by curtains hung at random places. Although there is a carpet, the floor is otherwise hidden underneath a white cloth, which extends to her make-up table. This table is surrounded by the same high and wide, empty grey walls. On the street, the unusual floor cover perseveres, now resembling a glossy dark tarpaulin instead of concrete (see fig. 2). The houses lining the street also do not seem made of brick or wood, but of two-dimensional painted cardboard. Even at the gambling table, almost unnoticeable because the image is populated by so many people, the background wall seems to be made of nothing but tarpaulin hung on a fence. The hallway through which Branigan follows the masked man is lined with thin plastic sheeting and supposedly leads to the orgy room, filled with scaffolding, aluminum foil, and various types of fabric (see fig. 5). The reason for these prop choices might be purely material: Given an empty and vacant studio, these coverings might have been the least costly and most effective solution to fashion these spaces into something recognizable. Indeed, Vernallis remarks how directors would select props from random storages expedited in good faith to the video set (106). The search for explanation notwithstanding, I am much more interested in the effect of these choices. Many of the props are borrowed from the domain of construction work, conveying a sense of unfinishedness. Especially sheets, tarpaulin, and foil also have a concealing effect, as their function is to hide and inhibit access. The spaces visible in the music video become but sketches of their inspirations, hasty constructions that signal their ephemeral quality to the viewer. Bedrooms, streets, and clubs become abstracted and uninhabitable; these prop choices work in tandem with the propulsive nature of the medium sound. These spaces do not obscure their fictionality but openly display their detachment from “real life.”

“Live Among the Creatures of the Night:” Reading Branigan’s Body in Space

To reiterate Susan Faludi’s claim, the feminist movement was undergoing a period of crisis in the early 1980s. Simultaneously, the new medium of the MTV music video is regarded by some scholars as a platform where different conceptions of femininity were presented and mediated. I position the music video of “Self Control” among these mediations, as it toes the line between transgression and regression in its staging and cinematography, iconography, and reception.

First, I revert to my argument on the circular narrative of “Self Control,” which positions the fictionalized Laura Branigan in a cycle of boring, uninspiring daytime and fulfilling, steamy nighttime. ‘Daytime Branigan’ is one that viewers barely encounter, except at the beginning of the music video. She is lounging in her chaise longue and holding a newspaper, which her eyes evade in favor of the air above. Her hand is moving from her private parts to her breasts, as the camera performs a rotation around her from a high angle. Static in comparison to the agile camera, and downgraded by its angle, she is almost relegated to the status of the furniture: an adornment, not an agent. Her absent gaze and slow movement, in convergence with the naked man in the background, however, allude to an act of transgression, of leaving this motionless shell for something more.3 Shonk and McClure have characterized the multiplicity of feminisms on early MTV as a harbinger of the third wave. A key message of these new feminisms was that “a woman could be sexual but not […] sexualized […] independent from the patriarchy but also enamored by a man” (Shonk and McClure 174). ‘Nighttime Branigan’ is a quiet embodiment of this idea, as she decides to actively seek erotic pleasure. Taking the idea of transgression quite literally, she disobeys the one-way sign on the street, deliberately walking in the other direction (fig. 6), and crosses a red traffic light (at least this is alluded to). Time after time, she decides to follow the masked man, who was, according to Branigan herself, supposed to personify the night (“Laura Branigan: Interview,” 3:37-49). Through the preceding context, her submission to the masked man (4:00) is presented as an act of her own volition and not as a surrender to the patriarchy.

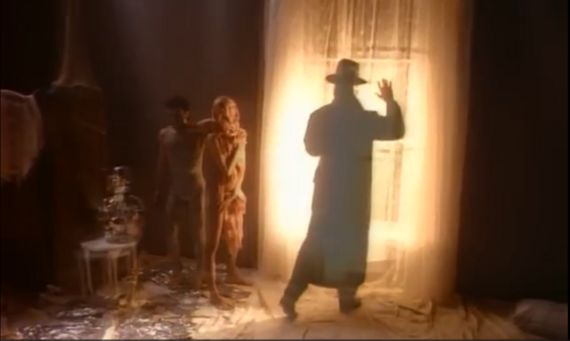

Transgression is also present on the level of lighting. The very first shot of “Self Control” shows a monochrome red screen, anticipating the repeated use of this color. When Branigan peeks through her curtains onto a silhouette of the cityscape, the black buildings are also lit by a red screen turning purple (fig. 7). This prompts Branigan to bite her finger in excitement and introduces the beguiling effect that red lighting has on her throughout the video. Similarly, once Branigan has applied her full make-up, the mirror lights redden and one of the ballet dancers appears to give a foretaste of the impending nighttime action (fig. 7). Still on the street, roadblocks are flashing red, and we see a red traffic light connoting the realm of the forbidden and prohibited. Unfazed by these signals of restriction, Branigan progresses to the club, lured by the masked figure she saw in the car, behind whom a red light glows (fig. 7). Although dressed in black and wearing a white mask, this figure remains entangled with the color red, as he is wearing red gloves on his hands, one of which he extends towards Branigan, asking her to descend to the floor of action (fig. 7). After spending the night with Branigan, the masked man disintegrates into sunlight. One last time, red light is being used when Branigan switches off her reddish lamp, symbolically ending the period of transgression (see fig. 7).

Red light as a symbol of the dangerous and alluring, the erotic, and the otherworldly, was also used in disco videos, prominently in the music video of Sylvester’s 1978 song “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” (fig. 8). Being used in such openly queer videos, red light does not only signify transgression, but more concretely the breaking of gender norms and the celebration of non-accepted forms of sexuality. Red light has been used to light queer spaces in the disco era, a tradition Branigan adopts in the “Self Control” music video.

While Laura Branigan certainly embodies a woman transgressing sexual norms and materializing her desire in the guise of night, this is not an unequivocally emancipatory portrayal, as her transgression is visually sanctioned in various ways. The most glaring moments of sanction are the two shots showcasing a puppet resembling Branigan in the bedroom. Between the beginning and ending of the video, the puppet undergoes a handful of meaningful changes. One of her eyelids is closed and a lash dangles from it, she has applied lipstick in a messy manner, and her neat hairdo has become tousled (fig. 9). This image not only contradicts a circular narrative of endless repetition, as it proves that the beginning and ending of the video are not identical, but also carries an almost moralistic undertone of lost innocence and order. Further examples of visual sanctioning are the shot in which the “creatures of the night” approach an apparently paralyzed Branigan in the hallway shot, which frames a frightened Branigan stumbling to escape arms reaching out to her. These scenes insinuate that “the night” might have been too much for Branigan, that she might come to regret her act of transgression. This is reminiscent of nostalgic sentiments for a time “before feminism,” which Susan Faludi posits as symptomatic of the 1980s.

I want to contrast this reading, which locates “Self Control” closer to the backlash described by Faludi, with a queer reading of the video provided by architectural scholar and techno DJ Simona Castricum. Castricum’s reading emphasizes how the video, for her, clearly evokes the queer nightclubs of her early adulthood, and through its pungent eroticism constructs “liminal spaces of permission, denial, shame and pleasure” (195). Although she laments the effects of censorship, the video still sufficed to transport a queer message and provide inspiration to “reject the control of the heteronormative and cisnormative world, […] to transgress external controls of sexuality and gender” (195). Reconsidering the Stepford Wives comparison by Sullivan, it appears that the video does not only carry text-intrinsic contradictions of enaction and penalty towards gender and sexuality-based transgression but has also prompted them in its reception.

“In the forest of my dreams:” Reading Editing in “Self Control”

Another parameter of film form foregrounded in “Self Control” is editing. The transitions between shots use innovative editing techniques – in particular, dissolves and the Kuleshov effect – which augment the logics of space inscribed into the video. The process of disorientation, already subliminally present in the realms of mise-en-scène and staging, is thus expanded to another parameter of the music video format.

Shots in “Self Control” are joined in a variety of ways.4 Most shots that relate to each other are joined by simple cuts, which means one image abruptly substitutes the next. When a new section is introduced, more elaborate techniques are used. The timing of such techniques here largely mirrors the spatial structure of the video as they mostly signal a change of location. The transition from bedroom to street, for instance, is executed through a dissolve in which the substitution of an image with another one occurs gradually. This impression of gradual change is heightened by the presence of the street in the last bedroom shot, through the window behind Branigan’s leg (0:50-54). It is almost as if the camera simply moved through the window, disregarding the height, and slowly descended. In addition, it also implies spatial continuity during a sequence whose parts were, in all likelihood, filmed on two distinct sets. Spatial limitations imposed on bodies by the physical world, such as the near impossibility to jump out of windows on higher storeys and remain unscathed, are insignificant to the omnipotent camera and, for a moment, the viewing body as well. Here, editing empowers the viewer spatially.

The next spatial transition is between the street and the bar and happens via a red hand as encountered at a traffic light (fig. 10). The hand shape first substitutes the street shot by blinking, then fades out to reveal the billiard table setting. Contrary to the home-street transition, no spatial relation is established. Viewers remain unaware of how Branigan moved from the street to the bar. The significance of the red hand exceeds simply symbolizing nightly transgression. As an editing technique, it obscures how the transgression happens on an orientational level. Questions like where Branigan goes to transgress, how she enters the bar, or where this bar is located are not answered in the video. In another instance of changing location, the transition between the dark hallway and the stairway is shown by Branigan touching the door with both hands. Instead of opening the door, the shot collapses and falls, giving way to the next shot. This combination of staging and editing simulates that Branigan’s manual power collapsed the film screen. The technique suspends the illusion of three-dimensionality and emphasizes how all video material remains two-dimensional. It also allows the camera to permeate the door without opening it. Here we encounter another dimension of music video editing, which, as Vernallis has reminded us, manipulates space beyond our physical capabilities. Through the use of these transitions, the video is structured and empowers viewers spatially while also exacerbating orientation and suspending bodily spatial limitations.

However, editing is not only relevant to the mediation of space in these larger transitions. In the cuts between shots set in the same environment, the video makers amply use the Kuleshov effect. For instance, this effect is repeated several times when Branigan spots the masked man: We see multiple shots of the man and Branigan staring into the camera and conclude they are looking at each other (e.g., 1:58-2:01, 2:37-44, 3:14-21). As viewers, we become encircled by the two figures and intrude into their intimate communication through glances. In “Self Control,” the Kuleshov effect thus establishes oppositions and communicates sexual tension, fear, enticement and temptation.

Finally, editing in “Self Control” is also used to join two shots to create the illusion that they are one. Examples of this technique include the figure that appears in the mirror as Branigan applies her makeup (fig. 7), the hallway where the masked man vanishes (2:10-12), Branigan disappearing in the white hallway (3:32), and the final departure of the masked man at the first sunlight (fig. 11). In another step that removes the video from an inhabitable reality, viewers are confronted with a space that can be left by dissolvement, which is at once liberating but also glaringly fictional.

The editing techniques employed by “Self Control” fashion the spaces of the video as liberating and transgressive because they exceed the spatial possibilities of the real world and enact alternate ways of moving and relating objects to one another. Simultaneously, however, the same techniques also relegate the video’s spaces to the domain of the fictional, emphasizing their constructed nature and unattainability. As a result, the images joined in Branigan’s music video do not provide a roadmap to transgressive spaces, but merely point to themselves.

Conclusion

My reading of “Self Control” shows how fragmented the representation of transgressive spaces grew over the course of MTV’s early years. “Self Control” was released when MTV had been on air for two years, by an artist whom critics have repeatedly characterized, in praise and scrutiny, as a commercial darling and a pet project of record executives. MTV’s target audience were young adults and one of the channel’s primary assets, according to Marks and Tannenbaum, was the celebration of youth and impermanence. MTV sold this not to the urban youth, who had ample opportunity to access transgressive spaces like nightclubs, but to the white, middle-class teenagers in suburban America. Accordingly, the video warps queer transgression to fit a female, white middle-class protagonist and portrays female sexuality ambiguously to both appease conservative voices and entice suburban teenage girls. The video also removes spaces of transgression from accessible physical space and transposes them to a television environment in which they generate profit for the booming channel. This forms part of the mission to “make it [MTV] their [the teenagers’] clubhouse” (Marks and Tannenbaum 2). Viewed against background, Branigan’s “Self Control” video, and others like it, present MTV as a privileged place to experience the enjoyment of demarginalization, corporeal freedom, and synchronized escape from the confinements of the work-home dichotomy.

Little is left of the lavish extravagance of queer disco spaces in “Self Control.” These spaces, which Luis-Manuel Garcia calls “a performative enactment of a world better than this one” (1) and Nadine Hubbs thinks can temporarily “collaps[e] … and revers[e] … social norms, hierarchies and castes” (239), have been distorted and burdened with commercial incentive. Nevertheless, song and video cannot be separated from the disco tradition, considering how Laura Branigan was commonly read as a post-disco starlet, likened most frequently to Donna Summer. This transformation of space coincides (not coincidentally) with an increase of conservatism and backlash towards progressive ideas, among them the backlash against feminism outlined by Faludi and exemplified by the ‘Disco Sucks’ movement, which explicitly shunned disco for its queer undertones. The erasure of explicit queerness as well as the ambiguous portrayal of female sexuality in “Self Control” thus also protect the video from public scrutiny. Nevertheless, queer notions of transgression still linger in the video in brief moments and fleeting symbols, as Castricum has argued.

“Self Control” is firmly situated in the processes of incorporation of disco spaces into the music industry of the 1980s and the manifestation of generic conventions. Both these processes cannot, as is evident from the music video, be regarded as independent of each other. Rather, they conditioned and influenced each other. Many of the music video’s early conventions, such as a focus on form, a lack of conclusive narrative, the disregard for the spatial logics of our physical reality and the liberatory function of music video space are also visible in “Self Control.” I believe that the connection I established to disco spaces and to the social, economic, and cultural position that MTV occupied in the social, economic, and cultural climate of the 1980s provides a promising starting point for explaining the emergence of these specific conventions.

Writing about the disco era of the 1970s in the wake of the 2020s disco renaissance, it seems evident that, although the music video genre has undergone immense transformations, ideas that were relevant to “Self Control” continue to linger today. The visual and sonic language of the disco era seems to remain an evocative tool which offers viewers experiences of transgression. My reading of “Self Control” has provided insight into how these representations can carry challenging baggage: They can erase queer imprints, concede to conservative criticism, and exploit utopian spaces of hedonism for a capitalist venture. Nonetheless, videos such as Branigan’s “Self Control” construct spaces for young audiences, including queer ones, to envision ways to move and relocate their bodies beyond the narrow possibilities of suburban environments – in the early 1980s and, seemingly, to this day.

Author Biography

Niklas Zabe (he/him) is currently pursuing a Master of Arts in North American Studies as well as a Master of Education in the subjects of English and Geography at Leibniz University Hannover. He completed his bachelor’s degree in 2023 with a thesis on two music videos. His research interests include popular American culture, queer studies, and the study of space. Outside of his academic pursuits, he is fond of cats, food, and a good night’s sleep.

Works Cited

Bordwell, David, et al. Film Art: An Introduction. 12th edition. McGraw-Hill Education, 2020.

Castricum, Simona. “Music as a Site of Transing.” Queering Architecture: Methods, Practices, Spaces, Pedagogies, edited by Marko Jobst and Naomi Stead, Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023, pp. 193-209.

Dyer, Richard. “In Defence of Disco.” Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian and Queer Essays on Popular Culture, edited by Corey K. Creekmur and Alexander Doty, Duke UP, 1995, pp. 407-15. www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9780822397441-025/html.

Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. Crown, 1991.

Frank, Gillian. “Discophobia: Antigay Prejudice and the 1979 Backlash Against Disco.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 16, no. 2, 2007, pp. 276-306. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30114235.

Garcia, Luis-Manuel. “Richard Dyer, ‘In Defence of Disco’ (1979).” History of Emotions: Insights into Research, Nov. 2014, https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_2096668/component/file_2096667/content.

Holden, Peter. “Laura Branigan 1985: A Dream Artist for Atlantic.” Cash Box, 27 Jul. 1985. Pinterest, uploaded by Stig-Åke Persson, www.pinterest.de/pin/761038037056435485/. Accessed 22 Jul. 2023.

Hubbs, Nadine. “‘I Will Survive’: Musical Mappings of Queer Social Space in a Disco Anthem.” Popular Music, vol. 26, no. 2, 2007, pp. 231-44. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4500315.

Hunt, Dennis. “Along Came Laura Singing a La Donna: Instant Hit.” The Indianapolis News, 29 Dec. 1982. Pinterest, uploaded by Stig-Åke Persson, https://www.pinterest.de/pin/761038037056435346/. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

Keazor, Henry, and Thorsten Wübbena, editors. Rewind, Play, Fast Forward: The Past, Present and Future of the Music Video. Transcript Verlag, 2010. www.degruyter.com/isbn/9783839411858.

Klein, Amanda Ann. Millennials Killed the Video Star: MTV’s Transition to Reality Programming. Duke UP, 2021.

Korsgaard, Mathias Bonde. Music Video After MTV: Audiovisual Studies, New Media, and Popular Music. Taylor and Francis, 2017.

“Laura Branigan: [cc] Interview About Self Control Music Video Controversy. ET (1984).” YouTube, uploaded by Laura Branigan Forever-Matty, 2 Apr. 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=836TObjuj0I. Accessed 18 June 2023.

“Laura Branigan: Interview [cc]. PM Magazine (1984).” YouTube, uploaded by Laura Branigan Forever, 30 Oct. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=fANpGa9NjOo. Accessed 29 July 2023.

“Laura Branigan - Self Control (HD Remastered).” YouTube, uploaded by Remastered videos, 24 Aug. 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pd_1j55V6Fw. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

Lewis, Lisa A. “Being Discovered: The Emergence of Female Address on MTV.” Sound and Vision: The Music Video Reader, edited by Simon Frith et al., 1993. Taylor and Francis, 2005, pp. 111–30.

Marks, Craig, and Rob Tannenbaum. I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution. Penguin Publishing Group, 2011.

Ray, Michael. Disco, Punk, New Wave, Heavy Metal, and More: Music in the 1970s and 1980s. Britannica Educational Publishing, 2013.

Reynolds, Simon. “In Praise of ‘In-Between’ Periods in Pop History.” Slate, 29 May 2009, https://slate.com/culture/2009/05/in-praise-of-in-between-periods-in-pop-history.html. Accessed 17 July 2023.

Shonk, Kenneth L., and Daniel Robert McClure. “Waveless: MTV and the ‘Quiet’ Feminism of the 1980s.” Historical Theory and Methods Through Popular Music, 1970-2000: “Those Are the New Saints,” edited by Kenneth L. Shonk and Daniel Robert McClure, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017, pp. 171–98.

Sullivan, Jim. “Branigan: A Robotic Form of Eroticism.” Boston Globe, 22 July 1985. Pinterest, uploaded by Stig-Åke Persson, https://www.pinterest.de/pin/761038037056435462/. Accessed 3. Aug. 2023.

“Sylvester - You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real).” YouTube, uploaded by Sylvester, 6 Sept. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gD6cPE2BHic. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

Thompson, Graham. American Culture in the 1980s. Edinburgh UP, 2007.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. U of Minnesota P, 1977.

Vernallis, Carol. Experiencing Music Video: Aesthetics and Cultural Context. Columbia UP, 2004.

Copyright (c) 2024 Niklas Zabe.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

1 For Dyer, an example of phallocentric music would be rock music.

2 How exactly disco remained influential in early 1980s pop music is explored succinctly by Reynolds.

3 Indeed, as the body is already in bed behind her, this might also temporally fall into the morning, closing the circle. The concrete temporality of these introductory shots remains somewhat mysterious. I understand this as deliberate, since circles, after all, never end.

4 The classification used here is taken from Bordwell et al. (217).