Introduction

If it were not for my exhausted body, this paper would not exist. If I had not listened to my exhaustion, these pages would be blank. But I am not all mind, just as I am not all body. The two nourish each other. “[A]ll theories come from individuals with their own personal, subjective, and embodied experiences and […] these experiences almost inevitably feed into their theories” (Amodeo). It is through my deeply embodied experience of exhaustion and the need to recharge that Rebecca Hall and Hugo Martínez’ Wake: The Hidden History of Women Led Slave Revolts found its way into my life. Its description had managed to get me perked up again because it reminded me of the class on autotheory that I was taking. As I began flipping through the pages of the graphic narrative, I discovered that it was not only reminiscent of my class but also of one specific book that I had read for it: Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments.

Both works are written by women historians who are portraying the previously undocumented lives of rebellious black women. In Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Saidiya Hartman traces the stories of young, black women at the beginning of the twentieth century, thereby choosing to give space and voice to those who, in their ordinary yet beautiful rebellion, are threatened to be erased by a history that was not written to include them. Similarly telling a ‘forgotten’ story about rebellious women, Wake depicts Rebecca Hall’s struggle of unearthing details about the lives of the women warriors who led slave revolts during the Middle Passage. Both authors fill the gaps of the archive and choose to tell their stories through a lens that Hartman refers to as “sensory” (xv), and which I am going to simply call ‘affective.’ I argue that this affective quality of both Wayward Lives and Wake is made possible through the authors’ autotheoretical, transdisciplinary engagement with the material.

Seeing as the two narratives have so much in common but are executed in quite different styles, I am interested in examining how lived experience and the affective quality that accompanies its portrayal can be evoked in different ways in works of autotheory. I argue that autotheory’s existence in the liminal spaces between personal and theoretical, “research and creation” (Fournier 10) makes for an ideal birthplace for affect.

In the following, I will first be looking at the place of the body in autotheory, before then diving into the field of affect theory in general and, following, its connection to graphic narratives such as Wake. Lastly, I will apply my findings to an analysis of Wayward Lives and Wake. Where fitting, I will supplement my theoretical research with the addition of my own lived experience as another layer of knowledge.

Affect, Autotheory, and Comics

In the following effort to determine the role that affect plays in, as well as, potentially, beyond both of these works, I am going to discuss Rebecca Hall’s Wake and Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives as works of autotheory. To begin with, I am interested in what exactly we are dealing with when we are talking about ‘autotheory.’ According to Lauren Fournier,

autotheory seems a particularly appropriate term for works that exceed existing genre categories and disciplinary bounds, that flourish in the liminal spaces between categories, that reveal the entanglement of research and creation, and that fuse seemingly disparate modes to fresh effects […]. [A]utotheory might best be understood as fundamentally transdisciplinary. (10)

This definition certainly leaves room for interpretation. Fournier seems to suggest that any work in which theoretical findings are being expressed in ‘fresh’ ways could be regarded as autotheoretical. This definition then still lacks the ‘auto’-part of the work/word. Elaborating on her definition, Fournier further writes that “[t]he autotheorist shuttles between self and theory – political theory, linguistics, poststructuralism, affect theory, performance theory, aesthetics, gender – using firsthand experience as a person living in the world as the ground for developing and honing theoretical arguments and theses” (32). That is, the lived experience of the autotheorist lays the groundwork for an expression of arguments that transcends disciplines. Dan Harris agrees with Fournier’s notion of autotheory’s liminality but gets more specific when he clarifies that “[w]hile autotheory makes a case for the productive enmeshment of personal and theoretical, it does so in a work of written art that is modeling the affective nature of creativity […]. It also challenges the still-pervasive myth of objectivity in academic writing” (22). Here, Harris identifies two interesting elements of autotheoretical works. Firstly, he points out the affective quality that can be found in autotheory’s creative expression. It could be argued that it is autotheory’s very centering of lived, embodied experience that enables this rise of affect. Ralph Clare’s concurrence of Harris’ emphasis on the role of affect in autotheory surely points towards this conclusion of mine; he describes autotheoretical texts as those “that do not simply blur the distinctions between fiction and non-fiction, […] but, more importantly, that self-consciously attempt to deal with theory in a more practical, affective, and pragmatic manner, particularly by stressing the value of embodied experience” (90). But Clare also takes up Harris’ second point – the challenge that autotheory poses to ideas of objectivity in academic works – when he mentions autotheory’s blurring of fiction and non-fiction. For, clearly, anything that exists in the space between the two could most definitely not be regarded as ‘objective.’ I will revisit this point of enmeshment of fact and fiction later in this chapter in the context of graphic narratives, but before I do so, I want to further explore autotheory’s connection to affect.

What Clare calls the “in-between-ness” (104) of autotheory may be exactly the point where affect can be found since, according to Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, “[a]ffect arises in the midst of inbetween-ness […] and resides as accumulated beside-ness. Affect can be understood then as a gradient of bodily capacity” (1-2). They, too, are pointing towards the role of the body in affect and yet, it is not entirely clear what this thing called affect even is until they go on to frame “[a]ffect [a]s in many ways synonymous with force or forces of encounter” (2). Here, the body’s necessary presence becomes more apparent, for what other, if not bodily, containers could encounter each other; where else could forces be felt if not in the body? This, then, raises a question: If affect is such a bodily phenomenon, can it even be evoked through such a mind-full activity as reading a text?

Following Sara Ahmed’s notion that “affect does not reside positively in the sign or commodity, but is produced only as an effect of its circulation” (“Affective Economies” 120), one could suspect that such a circulation is also possible through different media. Elspeth Probyn supports this idea when exploring the role of shame in academic writing. She asserts that “writing affects bodies. Writing takes its toll on the body that writes and the bodies that read or listen” (76). Probyn even goes as far as to declare that “[t]hinking, writing, and reading are integral to our capacities to affect and to be affected” (77), and therefore dismantles Cartesian notions of mind-body dualism, where writing and thinking are categorized as purely logical, non-bodily activities. Although Simon O’Sullivan claims that “you cannot read affects, you can only experience them” (126), he also points out that art (which I would argue autotheoretical works to be part of) is “a bundle of affects […] waiting to be reactivated by a spectator or participant” (126). He then continues to declare that “[a]rt is less involved in making sense of the world and more involved in exploring the possibilities of being, of becoming, in the world. Less involved in knowledge and more involved in experience, in pushing forward the boundaries of what can be experienced” (130). While I do agree with this idea of ‘art-as-experience,’ I nonetheless want to call attention to O’Sullivan’s disregard of (embodied, lived) experience as a form of knowledge itself, since it is this very disregard that autotheoretical works are challenging.

Turning from affect in written narratives to its role in graphic narratives such as Hall’s Wake, I would like to reframe reading not as an activity of thought but, first of all, of perception. As Karin Kukkonen elucidates in her essay about embodiment in comics, “perception is not only exclusively visual, but involves the entire body […]. [It is] not a detached contemplation of the world or an achievement just of eye and brain. Considering the bodily activities of characters, readers can get a sense of how they perceive the [world] around them” (51). It is through this perception that affect can be transported off the page and thus arise in the reader. Kukkonen bases her claims on research in the areas of mirror neurons and motor resonance, which “suggest that it is likely that readers of comics, too, experience bodily echoes of the motions and actions they observe” (53). Andrew J. Kunka points towards a similar ‘force of encounter’ (to use Gregg and Seigworth’s wording) when writing that “[t]he interactive nature of comics […] can help develop a sympathetic connection between reader and subject, enhancing the intense experience of trauma or the humor of the mundane” (2). This is particularly noteworthy since, according to Hillary Chute, autobiographical works are “the dominant mode of current graphic narrative” (456), meaning that the experience portrayed in the work is, in most cases, of autobiographical nature and thus exists in relatively close proximity to works of autotheory.

While comics or, as I am choosing to refer to them for reasons of inclusiveness, graphic narratives, were long “understood as an antielitist art form” (Chute 455), works such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis have helped to bring the genre acclaim (Chute 457) as well as scholarly attention. Chute suggests that the genre’s “compounding of word and image has led to new possibilities for writing history that combine formal experimentation with an appeal to mass readerships. Graphic narrative suggests that historical accuracy is not the opposite of creative invention; the problematics of what we consider fact and fiction are made apparent by the role of drawing” (459).

This argument is especially of interest to me since both of the works I am going to analyze are written by historians who are, through their works, challenging these very boundaries between ‘historical accuracy’ and creative invention or, as Hall calls it, making “educated guesses about what happened” (ch. 2). Not only are graphic narratives particularly suited to challenging such boundaries, but Chute even declares that “[t]he most important graphic narratives explore the conflicted boundaries of what can be said and what can be shown at the intersection of collective histories and life stories” (459). In addition, she describes graphic narrative’s ability to “envision” (459) the everyday reality of women’s lives, which, as I will show in my later analysis, is something that can be observed in Rebecca Hall’s Wake. Chute argues that while these realities are rooted in personal experience, they are also “invested and threaded with collectivity” (459) – this, too, is a part of Wake that I will analyze later in this paper. In the case of Wake, but surely in many other autobiographical narratives as well, this collectivity does not just extend sideways but also back into the past, taking up the (hi)stories and experiences of ancestors and incorporating them into the present narrative and reality. The “ability of comics to spatially juxtapose (and overlay) past and present and future moments on the page” (Chute 453) makes the genre especially fit for portraying such connections. Here, the aforementioned mixing of fact and fiction becomes especially apparent: when, for instance, autobiographical (including autotheoretical) graphic narratives portray felt presences of ancestors as actual presences, the boundaries between fact and fiction become blurred.

Just as is the case in autotheory across all kinds of different media, “comics autobiography allow[s] the artist to structure the narrative to correspond to a larger, emotional [or, as I would argue, affective] truth” (Frederik Byrn Køhlert qtd. in Kunka 8). As Kunka concludes, it therefore reveals the very truth that there is no such thing as absolute truth, as what we mean when we talk about truth is always necessarily “mediated and unreliable” (10). It is the hybridity of graphic narratives, as well as, I argue, autotheory, that enables it to “challenge […] the structure of binary classification that opposes a set of terms, privileging one” (Chute and DeKoven 769).

Now that I have hopefully been able to make clear the connection between autotheory and affect, as well as the potential of graphic narratives to bring out the affective quality of embodied experience, I will turn to Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Rebecca Hall’s Wake to analyze the role of affect in two different forms of genre-transcending works. After all, as Jane Tolmie reminds us, “[t]here is an aesthetics of affect, not an inevitable or natural emotional side effect but a deliberate result of artistic decisions” (ix) – it is these very artistic decisions that I am going to examine more closely.

Affect in (and around) Wake and Wayward Lives

One way in which artistic decisions can create affect in autotheory is beautifully demonstrated in Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. The fact that there is, indeed, a deliberate artistic decision behind Hartman’s work becomes apparent on the very first pages of the book. In “A Note on Method,” Hartman explains that “[t]he aim is to convey the sensory experience of the city and to capture the rich landscape of black social life. To this end, I employ a mode of close narration, a style which places the voice of the narrator and character in inseparable relation, so that the vision, language, and rhythms of the wayward shape and arrange the text” (xv-xvi). Already, we can sense the potentially affective layer of the book, with words such as ‘sensory,’ ‘relation,’ ‘vision,’ and ‘rhythm’ alluding to a centering of bodily experiences. Not only is Hartman trying to give space to those whose voices and presences have been crushed by the archive, but she is doing so in a way that values their perspectives and centers their experiences (xv, xvi). Instead of merely glancing at these wayward lives, the reader – through Hartman’s careful crafting – is invited to step into the crowd and experience what life feels like inside of its center.

To begin with, Hartman guides the reader into the “ghetto [a]s a space of encounter” (4), the place where they are going to encounter ‘wayward’ characters. This guidance is especially necessary since, in this part of the city, “[t]he experience is too much” (4) – therefore it is only natural that “[t]he senses are solicited and overwhelmed. Look over here. Let your eyes take it all in” (6). Hartman encourages the reader, brings to attention the fact that to really perceive, instead of just noticing something, requires a certain level of active engagement. Now that the readers are, hopefully, immersing themselves into the experience provided through Hartman’s imagination, she plunges into a row of sensory descriptions:

What you can hear if you listen: The guttural tones of Yiddish making English into a foreign tongue […]. The eruption of laughter, the volley of curses, the shouts that make tenant walls vibrate and jar the floor […]. The rush of impressions: the musky scent of tightly pressed bodies dancing in a basement saloon; the inadvertent brush of a stranger’s hand against yours as she moves across the courtyard; a glimpse of young lovers huddled in the deep shadows of a tenement hallway; the violent embrace of two men brawling; the acrid odor of bacon and hoe-cake frying on an open fire; the honeysuckle of a domestic’s toilet water; the maple smoke rising from an old man’s corncob pipe. A whole world is jammed into one short block crowded with black folks shut out from almost every opportunity the city affords, but still intoxicated with freedom. The air is alive with the possibilities of assembling, gathering, congregating. (7-8)What you can hear if you listen: The guttural tones of Yiddish making English into a foreign tongue […]. The eruption of laughter, the volley of curses, the shouts that make tenant walls vibrate and jar the floor […]. The rush of impressions: the musky scent of tightly pressed bodies dancing in a basement saloon; the inadvertent brush of a stranger’s hand against yours as she moves across the courtyard; a glimpse of young lovers huddled in the deep shadows of a tenement hallway; the violent embrace of two men brawling; the acrid odor of bacon and hoe-cake frying on an open fire; the honeysuckle of a domestic’s toilet water; the maple smoke rising from an old man’s corncob pipe. A whole world is jammed into one short block crowded with black folks shut out from almost every opportunity the city affords, but still intoxicated with freedom. The air is alive with the possibilities of assembling, gathering, congregating. (7-8)

If one accepts Hartman’s invitation to linger in these places instead of just rushing through them, it is possible to make use of one’s bodily capacity to be affected by the words on the page. Especially through the choice of accumulating all these impressions, Hartman manages to make the city palpable. After having thus set the scene, she goes on to introduce (in what could be classified as twenty short stories) a set of characters she encountered during her research as a historian and portrays their lives. While each of these characters would be deserving of attention, I want to focus on the one whose encounter left me the most affected.

The first time I saw the girl, I did not see her at all. It was late at night on a weekday when I – in need of something I could immerse myself into to get distracted from the heaviness that can be my very own personal life – sat down at my desk and read the chapter from Wayward Lives that had been assigned for our class on autotheory. When I returned to my desk from a water refill break, I noticed something strange on the screen that was illuminating my by-now-dark apartment: a weird, senseless pattern of colors. At first, I thought I was simply so tired that I was imagining things, then, that something was wrong with my screen, but as I got closer, I realized that it was the text itself that looked wrong. Something must have gone wrong with the scanning of this particular set of pages. Relieved that neither my vision nor my laptop were impaired, I continued reading. It was only when I had finished the chapter that I realized the text was missing something: the study questions I had received for the text made mention of two photographs, while I had only seen one. Confused, I scrolled back – until I noticed my mistake and felt a wave of guilt wash over me. What I had explained as a result of madness; as something broken; the mistake was, in fact, a girl. A girl about the age of ten whose only remaining trace was the very photograph I had so horribly failed to notice in the background of the text. That night, I spent a long while ruminating on my experience of not-seeing the nameless girl. Was this not exemplary for most encounters she had probably had in her lifetime? Through all of this guilt, confusion, affect I was experiencing that night, there was something that I only noticed a week later when re-reading the text in preparation for class. In the very first lines of text covering the girl, Hartman relays wondering: “Was it possible to annotate the image? To make my words into a shield that might protect her, a barricade to deflect the gaze and cloak what had been exposed?” (26) – by my not-seeing the girl, Hartman had achieved exactly what she had hoped to. First, through speculating what the girl’s experience had felt like, Hartman had made my skin crawl in response to her questions:

Anticipating the pressure of his hands, did she tremble? Did the painter hover above the sofa and arrange her limps? Were his hands big and moist? Did they leave a viscous residue on the surface of her skin? Could she smell the odor of sweat, linseed oil, formaldehyde, and clothes worn for too many days? Did she notice the slippers, tattered shirt, and grubby pants, and then become frightened? Had the other models left their imprint in the lumpy surface, the oily patina of the upholstery, and the rank musty odor? (26)

Then, Hartman had made sure to protect the girl from further harrowing encounters by creatively using her own words as a barrier, leaving exposed only the haunting feeling of the girl’s experience. When discussing the text in class the following day, I learned that I was not the only one whose gaze Hartman had been able to successfully avert. In our Zoom breakout room, several fellow students stated having needed the guidance of the study questions to break through the barrier of words that Hartman had set up. However, one student in particular did not seem to experience Hartman’s artistic choice as the same kind of successful protection that it had come to resemble for me. Although they, too, had failed to notice the girl at first, upon realizing what lay hidden behind the words that their eyes had grazed, the student became filled with shame and rage – shame because they had involuntarily spent minutes staring at the naked body of a child, rage because Hartman had made them do so and, they felt, also subjected the girl to further violations. The affective forces were piling up in our virtual room and we got into a heated argument. I was almost yelling, trying to convince this other student of the girl’s protection, wanting to reach through the screen to grab them by the shoulders and shake them to make them realize that all was well. Before we could reach an agreement, though, our time in the breakout room was up and we had to end our discussion to return to the plenum.

While there were many aspects of Wayward Lives that left an impression on me (such as several other sections like the ones explored above), what stayed with me most deeply was this encounter and the way in which Hartman’s work had not only affected me, but also how her creative entanglement of image and text had affected this other student. Clearly, there was something happening in the gaps that the in-between-ness of autotheory afforded. Today, I would consider this ‘something’ the emergence of affect.

Exploring affective qualities in another autotheoretical work that creatively plays with both image and text, I am now turning towards Rebecca Hall and Hugo Martínez’ graphic narrative Wake. While I do not want to discredit Martínez illustrative contribution to this collaborative work, I am choosing to only make mention of Hall going forward, since it is her lived experience that supplies both the ‘auto’ and the ‘theory’ to the work. Just like Hartman is reading archival documents “against the grain […] in order to narrate [her] own story” (34), Hall had to “read between the lines” (ch. 2) of the archive to come across the women whose stories she is sharing in Wake.1 Where Hartman mainly inserts her presence to translate her characters’ experiences to the reader, Wake centers more clearly on Hall herself. As such, the book portrays not only the findings of Hall’s research but also illustrates the ways in which her work finds, affects, and guides her in both her professional and personal life. While doing so, there is a continuous emphasis on the role of her personal (some might say subjective), embodied experience.

Already in the prologue, Wake portrays Hall’s motivation behind her work: A two-page spread relays a revolt on a slave ship, and we see a woman escaping her capturers by jumping into the water (fig. 1). On the next page, we follow her journey underwater, diving across a few panels until a set of hands that looks just like hers is grabbing the sleeping Rebecca Hall. In the next panel, Hall is wide-awake, a haunted look on her face, and two captions inform the reader: “I am a historian. And I am haunted” (prologue). While this sequence does end with a verbal explanation, it is the graphic representation that relays the most information and makes Hall’s affective truth of physically feeling haunted, of being reached by and connected to the past, evident.

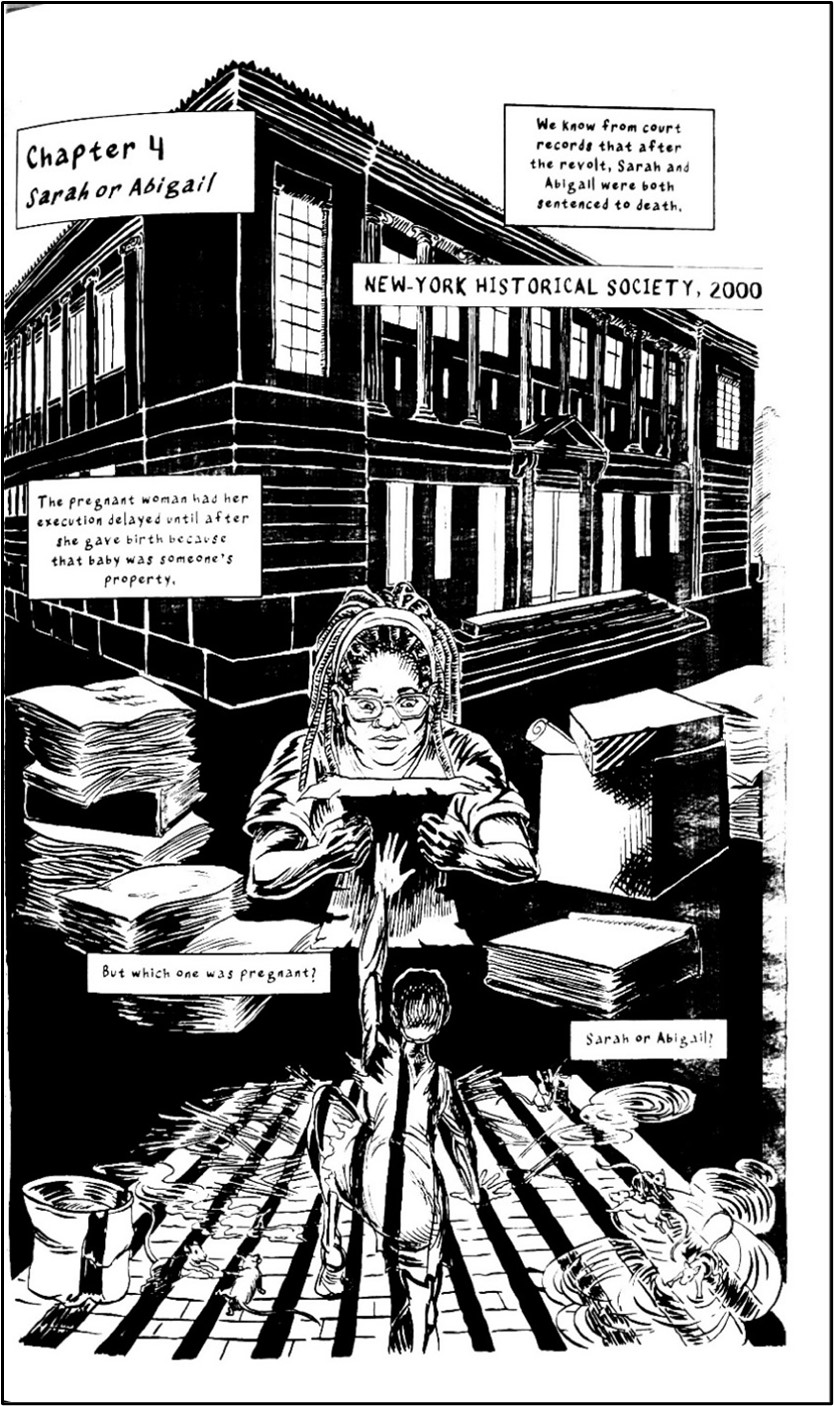

The beginning of chapter four further accentuates the fact that Hall’s research is affecting her. A splash portrays Hall, surrounded by stacks of court records, trying to trace the journey of three enslaved women who had been imprisoned post-revolt (fig. 2). The bottom part of the panel depicts one of these women pushing herself up from the dungy floor of her cell and reaching towards Hall. The illustration, which utilizes a set of parallel lines to guide the reader’s gaze directly to the woman’s hand, overpowers the panel’s captions and thus centers Hall’s embodied experience. She is conducting her research because, perhaps, she feels like she can help the women escape their imprisonment by reading archival “documents against the grain” (ch. 4) and trying to uncover their stories – or because, even if she cannot help after all, she still feels haunted by the past.

That this work is anything but easy becomes apparent later in the chapter. Sitting in the library, still fenced in by stacks of documents, Hall is first depicted as being surrounded by empty space before the composition becomes reversed and we see a bustling library surrounding Hall’s by-now empty body (fig. 3). A caption reading “I can’t find her, I’ll never know what happened to Sarah or Abigail” (ch. 4) serves as an explanation to this portrayed experience of first ungroundedness, then emptiness. That the affect her work has on Hall does not ‘stay in the office’ when she leaves at the end of the workday becomes apparent over the next couple of pages. The reader follows Hall slowly coming ‘back into herself’ and going home: On the way, her surroundings become more and more warped and overwhelming until she is enveloped by complete darkness – a darkness that is still present when she eventually arrives home and curls up on her bed (fig. 4). All of this transpires without a single caption or speech bubble and makes this portrayal of depression especially visceral.

Wake, however, makes a point of equally showcasing the ways in which Hall’s affective entanglement with the (hi)stories of black women is a source of strength for her. Chapter six depicts how, following a conversation with one of her students about Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Hall is visibly upset by the story’s powerful message about the trauma of slavery – that to kill one’s child would be better than to subject it to life as a slave. Having written down in her notebook that “[o]ur memories are longer than our lifespans[.] Haunting is what makes the present waver” (ch. 6), Hall is standing in front of the sink, splashing hot water into her face, when she looks up into the steam-covered mirror to find her reflection distorted: a woman appears holding an arrow, ready to fight (fig. 5). Here, again, the illustrations depict what can be characterized as Hall’s embodied knowledge: that those who came before her are somehow still alive inside of herself.

In the following, the chapter focuses on Hall’s grandmother, illustrating how both her grandmother’s spirit as well as “the spirit of [her] ancestors, including those in slavery” (ch. 6) are not only present in Hall’s life, but help her feel like she can survive “today” (ch. 6). The ensuing portrayal of the life of Hall’s grandmother, Harriet Thorpe, not only registers her struggles but, more than anything, her strength as well as the ways in which she managed to still find joy amidst misery. In a scene where Thorpe’s son mentions his mother working two jobs, which must clearly leave her tired, she responds by starting to dance, demonstrating that her assurance, “No ways tired!” is to be taken seriously (fig. 6). Here, too, the graphic addition to the text makes all the difference: Thorpe’s energized body speaks its very own language, affectively informing both her son and the reader of a truth that transcends any literal expression of truth.

It is this element of joy that makes me return to Wayward Lives, where sensuous pleasure shares center stage with the struggle of daily life. For instance, one story portrays the ways in which, no matter how bleak the circumstances,

[i]n its broadest sense, choreography – this practice of bodies in motion – was a call to freedom. The swivel and circle of hips, the nasty elegance of the Shimmy, the changing-same of collective movement, the repetition, the improvisation of escape and subsistence, bodied forth the shared dream of scrub maids, elevator boys, whores, sweet men, stevedores, chorus girls, and tenement dwellers – not to be fixed at the bottom, not to be walled in the ghetto. Each dance was a rehearsal for escape. (Hartman 306)

By portraying the lives of these young, black women in all of their affective layers, Hartman refuses to paint a simplistic, judgmental picture, instead “offer[ing] an account that attends to beautiful experiments” (xvi). Hall ends Wake on a similar note of empowerment when declaring that “[w]hen we go back and retrieve our past […] we empower and bring joy to our present” (ch. 10), thereby accentuating the value and power of the affective “forces of encounter” (Gregg and Seigworth 2) that shape human lives.

Conclusion

I have attempted to show through my analysis of Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Rebecca Hall and Hugo Martínez’ Wake that autotheory’s existence in the liminal spaces between personal and theoretical, “research and creation” (Fournier 10) makes for an ideal birthplace for affect. Especially in cases where the autotheorist themselves supplements their theoretical work with their own, lived experience, they can make use of autotheory’s transdisciplinarity to allow affect to enter the page.

As we can see in Wake, autotheoretical works can productively employ creative forms of expressions, mixing genre and media to portray the autotheorist’s own experience, therefore making palpable the “forces of encounter” (Gregg and Seighworth 2) that fuel and affect both professional and personal lives. But even when autotheorists put less emphasis on their own existence, it is still this very existence that enables works of autotheory to be infused with an affective quality. In cases such as Wayward Lives, autotheorists’ embodied connection to their material makes possible what Hartman so powerfully applies: by placing herself inside of the circle of those whose lives she is portraying, by asking questions and imagining not only what the lives she is researching have looked but, almost more importantly, felt like, Hartman manages to fill the page with affective forces. However, Hartman also seems aware that in order to transport these affects off the page, readers must really immerse themselves into what they have been offered. Just as Hartman guides her readers to look, hear, feel, Hall, too, seems aware of the readers’ need to pause and feel their way into the affective when she writes: “[m]aybe, if we listen carefully, we can hear [the voices of the slaves]” (ch. 8), thus placing emphasis on active engagement instead of passive consumption.

In any case, it seems that the in-between-ness of autotheory, both in regard to form and content, is especially suited for causing a circulation of affect. As my own experience with reading and discussing Wayward Lives demonstrates, texts can, indeed, affect their readers in some way or another. However, this encounter also reveals that, while works of autotheory can have such affective effects, the kinds of affects that arise from a piece of autotheoretical work can vary drastically. This does make sense if we take into consideration that, as Sara Ahmed points out, “bodies do not arrive in neutral, if we are always in some way or another moody, then what we will receive as an impression will depend on our affective situation” (“Happy Objects” 36). Additionally, the ways in which we are affected by something are highly dependent not only on our current state, but also on our personal past histories, encounters, and experiences. That being said, my point remains that, in autotheory, lived experience as both knowledge and personal truth can be expressed through a creative mingling of genres and media. And that, I strongly feel, is a whole kind of pleasure itself – a pleasure which can then fuel the ways in which we live, work, and affect.

Author Biography

Marielle Tomasic is a master student of North American Studies and holds a B.A. in English and Philosophy from Leibniz University Hannover. Besides being a student, she is also an editorial assistant for a publishing house. In her research, she is particularly interested in literature that crosses the boundaries of fact and fiction as well as those between the personal and the theoretical, and thus focuses on studies of autotheory, autofiction, life writing and liminal studies.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. “Affective Economies.” Social Text, vol. 22, no. 2, 2004, pp. 117-39.

---. “Happy Objects.” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 29-51.

Amodeo, Gabrielle. “Trauma and Autotheory in an Expanded Practice of Life Drawing.” Arts, vol.11, no. 5, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11050080.

Chute, Hillary. “Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative.” PMLA, vol. 123, no. 2, 2008, pp. 452-65.

---, and Marianne DeKoven. “Introduction: Graphic Narrative.” Graphic Narrative, special issue of Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 52, no. 4, 2006, pp. 767-82.

Clare, Ralph. “Becoming Autotheory.” Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory, vol. 76, no 1, 2020, pp. 85-107.

Fournier, Lauren. Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism. MIT Press, 2021.

Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory J. Seigworth. “An Inventory of Shimmers.” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 1-28.

Hall, Rebecca, and Hugo Martínez. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. Lettered by Sarula Bao, Particular Books, 2021.

Harris, Dan. Creative Agency, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women and Queer Radicals. Serpent’s Tail, 2021.

Kukkonen, Karin. “Space, Time, and Causality in Graphic Narratives: An Embodied Approach.” From Comic Strips to Graphic Novels: Contributions to the Theory and History of Graphic Narrative, edited by Daniel Stein and Jan-Noël Thon, de Gruyter, 2013, pp. 49-66.

Kunka, Andrew J. Autobiographical Comics. Bloomsbury, 2017.

O’Sullivan, Simon. “The Aesthetics of Affect: Thinking Art Beyond Representation.” Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, vol. 6, no. 3, 2001, pp. 125-35.

Probyn, Elspeth. “Writing Shame.” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 71-92.

Tolmie, Jane. “Introduction: If a Body Meet a Body.” Drawing from Life: Memory and Subjectivity in Comic Art, edited by Jane Tolmie, U of Mississippi P, 2013, pp. vii-xxiii.

Copyright (c) 2023 Marielle Tomasic.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

1 Like many other graphic novels and comics sources, the edition of Wake cited in this article does not include page numbers. Because of this, parenthetical references to the text indicate book chapters instead of pages or page ranges. Where needed, I have included figures to illustrate my argument and to reference relevant parts of Wake’s narrative.